The southeast flank of Haleakala slopes into the Pacific; the Maui sky vaults over the southern horizon. About an hour from the nearest town in either direction along Piilani Highway, a few clustered houses comprise the village of Kaupo. Here the humid jungles of Kipahulu turn to dry grassland, and cattle roam the road. Looking like a Wild West town adrift at sea, Kaupo still has its cowboys and ranchers. Spots of blue show through bullet holes in the road signs. The exact population is a mystery: Some say a hundred, some say fifty—give or take forty—plus however many up in the hills who don't want to be counted.

The aesthetic here might be called Hawaiian Gothic, replete with trucks and sheds, hardware and horses. One property, though, stands in counterpoint to the warm atmosphere of decrepitude: Behind a black lava-rock wall, two ceramic panels depicting female figures in bright pastels grace a yellow stucco cabin. There's a sculpture of a headless woman and a tall red vase standing on a plinth. "Resta Studios," the stucco gate posts read. "Villa Tamarinda." Beneath the signage, a tile features the timeworn outline of a yellow dog on a red field, like the seal of a Roman household.

|

|

(LEFT) The gate to Villa Tamarinda, Piero Resta's Mediterranean-style home in Kaupo, Maui. (RIGHT) Resta was a bit of a Renaissance man; in addition to painting, he was an accomplished fashion photographer. Resta's shoot for Mademoiselle in NYC.

This was the home of the late Italian artist Piero Resta. Here, in Maui's wildlands, his art remained incongruously European: His faces alluded to the conciseness of Henri Matisse's; his outlined figures harked back to the weightlessness and pliancy of Marc Chagall's. Throughout his career, Resta produced over a thousand paintings, drawings and sculptures, first in a figurative style then later drawing from Cubism, Abstract Expressionism and geometric abstraction. "I've admired his fresh approach to painting, his deep devotion to Mother Nature, and his open attitude toward existence," says Ida Panicelli, the editor of Artforum from 1988 to 1992. She visited Resta in the early '90s, and he gave her a painting of a sea goddess. "She has protected me since. I cherish her, her energy still resonates," Panicelli says. While Resta's works have dispersed across Maui and the world, his largest work-his sanctuary, his "cathedral without walls," as he called it-is tucked back behind that stone wall.

A man, his gong and a pregnant woman appeared on Maui. Eight years earlier, the man had been living alone for a year in a driftwood hut on a sea cliff in Northern California, when he saw a woman in white on a dirt road. He thought she had come to him as a vision. Soon she began bringing him baskets of food. Piero Resta had found himself living inside a myth.

"When Truth Rings a Bell."

"Ancient and Future Cities of Light."

The year was 1970. The hut was two miles outside of Bolinas, just up the coast from San Francisco, then a hotbed of soul-searching hippies and poets. Soon Resta and the woman, Gail Wagner, started an avant-garde circus. Resta, the ringmaster, was a small man with an appreciative smile who preferred loose, bohemian clothes and the coif of an early Beatle. They called themselves alternately the Now Primitives and Circo del Sol, wore capes and grotesque masks, rode horses and frolicked in the woods. When Gail found out she was pregnant, the couple sought out the ideal place a child could be born. She had always wanted to go to Hawaii. A friend told them to fly to Maui and hitchhike to Paia, where they met a bearded man playing ukulele in a leopard-print speedo and cowboy boots, who pointed them somewhere Gail could have the baby. She delivered a girl in the pool of a nearby waterfall. "My parents were real hippies," says Bella Rosa Junglebird Flower Resta.

They took up in the jungle of Haiku, where Resta painted sporadically while dabbling in windsurfing and running restaurants. He loved parties and people, so he often made feasts for the house and struggled to turn a profit. The art began taking over his life anyhow, so he turned over the key to his landlord.

Resta had been keeping an eye out for land to buy, somewhere he would have more space and quiet. He read in a newspaper about a plot out in Kaupo that the owners were struggling to sell. It wasn't an attractive prospect—it hadn't rained there in quite some time. Resta and his son Luigi drove for an hour or two to the spot, then carved their way through the undergrowth with machetes. They found stone walls and a tiered pit that resembled an amphitheater. "They realized these were the structures of Maui's early inhabitants," says his son Enzo Resta. "They had civilizations there." Resta had found his place.

Even in remote Maui, Resta's artistic sensibilities remained definitively European, with influences of Matisse and Chagall as in his "Architecture of Flight,"

Two millennia ago Pliny and Ptolemy both wrote of the Roman colony of Iria, or Vicus Iriae, which became Viqueria, then Voghera. Resta was born there, in what is now the north of Italy, on August 3, 1940. His father, Luigi, was a fighter pilot for Fascist Italy in World War II. His mother, Grazie Becagli, raised him with a half-brother. When Resta was four years old, his father's plane was lost over Libya. "He was always kind of searching for answers," Enzo says. "He didn't have a lot of choice as a child." Piero was sent to military school, then studied architecture in Florence.

Later he sought out London's art scene, staying for six months and learning English. (Thirty-seven years later a British photojournalist named Paul Lowe sought Resta out and informed him that he was his son.) When Resta returned to Florence, he hawked leather goods in a street market. One day he was sitting in a cafe wearing a scarf and reading a book of Federico Garcia Lorca's poetry, when he made eye contact with Susan Hewlett, an American college student abroad for the summer. In his passable English he asked her to take a walk with him. The walk turned into a long trip around Europe, and in 1963 they moved to Manhattan, to Chelsea. Two sons, Enzo and Luigi soon followed. Resta worked as a photographer for L'Uomo Vogue, immersing himself in New York's art scene. He showed paintings in group shows. He walked through Washington Square Park and was struck by Allen Ginsberg reciting poetry. In 1967 he photographed Gerard Malanga, the poet and assistant to Andy Warhol, alongside fashion model Cathy Damien. "He was a kind man with a simpatico nature," Malanga recalls.

"Ode to Eyptology"

"And then he left on a journey with his art director," Enzo says. Resta, many attest, was quite taken with women. They were his artistic muse, the figures he painted most and his Achilles' heel. Hewlett left for Bolinas with the kids, and eventually Resta followed. "He realized he wasn't quite ready to leave it all behind," Enzo says. Still, the two split up but remained friends. Resta began living in the driftwood hut, met Gail and ran the circus. In 1978 he moved to Maui while his sons stayed in Bolinas.

For Resta, art went hand-in-hand with food. He started Piero's Garden Cafe in Paia, where he hosted poetry readings and concerts and his mother cooked Italian food, with a gallery space above the cafe. He and Gail opened a studio at the Pauwela Cannery in Haiku, where they sold art. Resta ran it like a workshop. Sometimes as many as five people in the studio worked on pieces he'd sketched. Gail made ceramics, fountains and columns, and sometimes assisted with his paintings. The pieces were signed "Piero Resta," but that didn't seem to trouble her. "It was all his stuff," she says.

As he acclimated to the island, he loaded his art with figures and bright colors. He embarked on a series, "Tropicana," which drew heavily from island imagery-palm trees and so on-but he kept it brief. "He didn't really need to create romanticized Hawaiiana to sell paintings to tourists," says Neida Bangerter, who met Resta at his restaurant and decades later curated a local retrospective of his work. "That wasn't his thing at all. But he also was raising a family of a lot of kids, and he was a businessman."

Resta often referred to his home as a “villa without walls,” says his son, Enzo Resta. “The idea that without walls, it was in its most expansive state.” One of Villa Tamarinda’s open-air rooms.

Resta worked under persistent financial pressure. "There were times when we had twenty bucks in the bank, and we would just look around and see what we had. And then we'd start making frescoes because all we had was cement," Gail says. Resta disliked letting galleries take a cut. "The way we sold art was by entertaining," Gail says.

At the time, windsurfing was growing more popular, and Maui's consistent winds drew European devotees. The thing they missed most was the European culture of food and art, "so the studio and the dinners became their culture," Gail says. Apart from Native Hawaiian culture, "there was just not much else happening." After Resta opened Piero's—now Casanova—in Makawao, a restaurant and eventual social hub, he made a lifelong friend there in famed promoter Shep Gordon, who had managed Alice Cooper and Groucho Marx, among others. Gordon and a number of his friends began acquiring Resta's art. "Most of my house is Piero's stuff," Gordon says. He has his paintings on the wall, sculptures in the yard and custom tile around his jacuzzi. "Happy paintings," he says. "It's hard to describe why you like a painting. It's like a song."

In late spring the mock orange blooms in Kaupo. Honeybees visit the flowers. The smell, like jasmine, is vast and nostalgic. Resta's black pickup truck is growing back into the grass. Here is an oasis, an extract of Italy with its olive trees and pastel stucco.

“The Dimensional Spirit of the Poet.”

For some twenty-four years, in between travels to Europe and the Mainland, Resta made his art here and entertained guests with wild parties. A cowboy on horseback used to check names at the gate, beyond which the yard winds through citrus trees with glazed ceramics scattered around the trunks—a face here, a wing there. An aging tent covers a table now strewn with glazed tiles, where Resta worked outside. Set farther back, an archway stands guard in front of a pavilion, resting on pillars colorfully painted and signed. The gong hangs, ready to be rung.

The pavilion-like a kitchen without walls-rises up in tiers with tables that would have once been busy with food, wine and people. The multi-day affairs, which attracted Maui's glitterati, verged on bacchic: At one party a bikini-clad woman covered with sushi lay on a table; guests plucked the food off her, recalls Resta's friend Giovanni Cappelli. A disco ball still dangles from the ceiling next to big boxy speakers that once blared Pavarotti. "The parties were a marketing strategy," Cappelli says. "People wanted to take a piece of him home with them, so they bought his art."

|

|

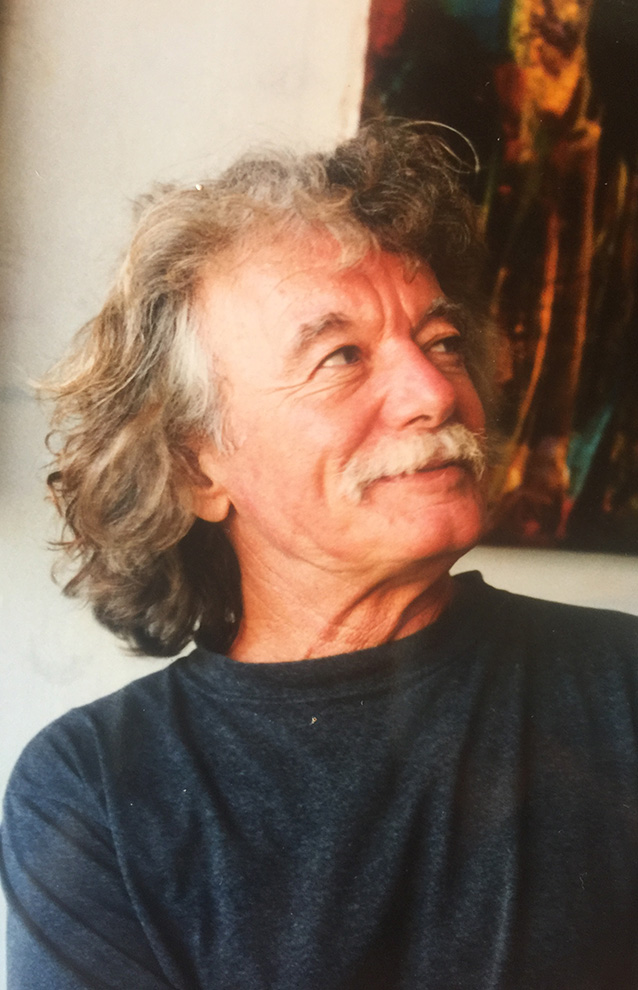

(LEFT) Resta; (RIGHT) "Entering the Golden Portal"

On a desk, a notebook page shows Resta's accounting: "Fontana 15,000 / Armonia 32,000 / Primavera 14,000 / Primavera 14,000 / Landscape 14,000 / Platter 900." An old scrap of a price tag on a string reads, "Acrylic on Canvas 50x72 $26,000.00." On another page Resta matched colors with their supposed healing properties: "turquoise = stimulates fisical body, circulation, vitalise nervous sistem ... coral stimulate 1 + 2 cakra, spine blood energise hart" and "perodot ... prevents fear." Resta believed art was "medicinal," that just the right colors and forms could have "physiological and behavioral benefits to humanity," Enzo says. He wanted his art to expand the viewer's sense of self as well as his own. (Buddha figures and carvings of Hindu gods inhabit niches on the property.)

To the right of the pavilion, a path leads to the amphitheater where Resta read poetry aloud; its semicircular tiers of lava rock are being reclaimed by the jungle. A stone stairway scales a grassy hill from the pavilion to "the bedroom," an open-air structure with a free-standing bathtub in the grass. From the road the fragmentary signs of Resta's world suggest something ancient, a halcyon Mediterranean idyll, but his inspiration had more primordial roots. "Piero thought of himself as a Roman," Bangerter says. Cappelli, himself Italian, clarifies: "I would call him more of a Tuscan kind of guy than a Roman kind of guy, but Tuscan in terms of deep roots that go back even before the Romans."

Since Resta passed in 2015, nature has begun reclaiming some of the grounds of Villa Tamarinda.

"Let the Spirit Exalt."

There aren't many reasons to come to Kaupo anymore. Two churches remain. A rotting schoolhouse was recently rebuilt. The general store is shuttered; from time to time a makeshift tent in its yard sells snacks, make-the-drive-home drip coffee and leather goods. A woman operating the stand moved to Kaupo seven years ago for "nothing," she says. "For the nothingness." She had just missed Resta, who died in 2015 from cancer.

Another woman who used to run the store remembers him. "He wasn't a recluse, but he was always busy, too, on the outside, going back and forth," she says. The world beyond Kaupo—"that's what we call the outside."